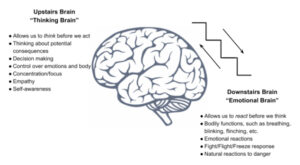

If you are a parent or have experience working with children, you’ve likely witnessed tantrums. Tantrums or outbursts may be triggered by a variety of things, including being told “no,” an inability to do something, transitioning away from a preferred activity, hunger, tiredness, losing a game, etc. During a child’s period of poor emotional control, it can even be challenging for adults to maintain a level head to aid children in returning to a calm state. Many times, adults may try to rationalize with a child’s emotions. “Just calm down! It’s not that big of a deal.” You may have noticed that even with the threat of a consequence or the promise of a reward, the child’s behavior doesn’t change and may even escalate further. The lack of success in trying to rationalize with a tantruming child comes down to brain development. The part of the brain in charge of controlling one’s emotions, the “upstairs brain,” continues maturing and developing up until about 25 years of age. Because of this, expecting a young child to fully control their emotions is setting an unrealistic expectation.

During periods of strong emotions, the “downstairs brain” or “feelings brain” becomes activated and takes control. This is the part of the brain in charge of our automatic responses, such as our fight, flight, or freeze response. Meanwhile, the “upstairs brain” or “thinking brain” becomes deactivated and is not able to process the ideas of consequences, rewards, or logic. In order to bring a child back to a calm emotional state, the “downstairs brain” needs to be soothed to allow for the “upstairs brain” to act. This process could include the use of deep breathing, squeezing a stress ball, squeezing putty, going for a walk, singing, hugging, listening to music, drawing, coloring, exercising, getting a drink of water, or even getting a snack (many of us know what it’s like to be hangry). Once the downstairs brain is soothed, the upstairs brain regains control and is able to process information. This presents an opportunity for a calm discussion about the trigger and what can be done differently next time. There are many ways to aid a child with learning to control their emotions and actions. Some recommendations include:

- Practice coping skills with your child when they’re calm to help prepare them to apply the strategies when they have a tantrum in the future. Spend some time outside blowing bubbles with your child. Practice taking a big inhale through your nose and a long, slow exhale as you blow your bubbles. Model the use of this coping skill by saying, “Wow! I bet breathing like this while I’m frustrated would really help!”

- Learn to identify your child’s triggers, and help them increase their own self-awareness of their triggers, too. Call attention to these moments when appropriate. “I’ve noticed that when your tower falls down, you seem frustrated.” “I’ve noticed that when it’s time to turn off your video games, we tend to argue. How about I give you a five-minute reminder next time?” Allow your child to express their feelings about their triggers.

- Intervene early. If we think of anger as being on a scale from 0 to 10, it’s much easier to go from a 3 back to 0 than from a 10 back to 0. You may notice the beginning of a tantrum when your child begins whining or grumbling, or when they become sassy or restless. Call attention to this and show empathy for your child. Take a deep breath, lower your tone of voice, and speak more slowly. Allow your child to feel seen, heard, and understood by asking them how they feel, nodding, showing a calm facial expression, and validating their feelings.

- Practice calming activities with your child during the early stages of frustration. This can be something as simple as gently tossing or rolling a ball back and forth. You can even incorporate breathing exercises into this activity by exhaling when the ball is thrown.

- Model the use of coping skills when you experience your own triggers. Children learn by observing. Parents need timeouts sometimes, too. “I’m feeling frustrated. I’m going to take a timeout to calm down.” When you’re frustrated, allow your child to hear you verbalize your feelings and your intended coping skill. “I feel upset. I’m going to take some deep breaths to help me relax.” “I feel stressed. I’m going to go for a little walk so I can feel calmer.”

- During the actual tantrum, remember that talking about the problem likely will not be effective since the downstairs brain is in control. Verbal interventions, such as talking, lecturing, threatening, rationalizing, or debating, are unlikely to work. The goal is to soothe the child’s emotions first, and then problem solve. Ensure that the environment is safe. Allow your child to have space if they need it.

- Don’t intervene too early by mentioning the problem again once your child is calming down. This may re-escalate your child. Allow your child to demonstrate that they are calm before intervening, and make sure that you are feeling calmer, too. You may notice that your child is calm when their voice becomes quieter, their body appears more relaxed, and they seem more like their “normal” self. Once everyone is back to 0, you can proceed with talking about what led to the outburst, how you each felt, and what you can each try to do differently next time. To ensure that you’re both calm, this may include waiting an hour, continuing with your routine, and discussing the problem later.

Although eliminating a child’s tantrums entirely may not be possible, these strategies can aid in reducing the intensity and length of tantrums. It’s never too late to try a new strategy. Every child is unique, and what works for one child may not work for another. Embrace the freedom to think outside the box to determine what helps both you and your child with controlling your emotions.

Devon Layfield, MSW, LCSW